AWDB speaks to Mella Jaarsma, a renowned Dutch artist based in Indonesia for the past 40 years recognised for her exploration of cultural and racial diversity. She works across various mediums, perhaps most notably within costume, performance, and food.

Deeply influenced by her experiences in Indonesia and her exposure to various cultural contexts, she examines the intersection of individual and collective identities in the modern world. Alongside her art practice, she is the co-founder of Cemeti Art House, a leading Indonesian gallery space hosting contemporary artists.

Jaarsma will be presenting her work ‘Surat Terakhir/Last Letter’ at ArtSG 2025 in Singapore. A series of costumes focusing on the colonial-era communication between Indonesia and the Netherlands, the costumes are printed with letters and postcards sent during the colonial period, many passing through the post office in Jakarta’s old town.

The work you have chosen to present at ArtSG, ‘Last Letter’, reflects on the evolution of communication and the passing of time. Do you harbour a sense of nostalgia for older traditions?

The inspiration for this piece was the main post office in Jakarta which was built by the Dutch during the colonial era, and its conversion into an art space, which is where the series was first exhibited. Rather than nostalgia, the work reflects how time is experienced in different periods, focusing on the various ways people have communicated and the act of waiting for messages in those times.

Many letters passed through the building, bearing within them so many stories and emotions. It has been the centre of communication for years and sending letters has been a very important mode of communication between Indonesia, and the Netherlands especially. When I started living in Jakarta in 1984, writing and posting letters to my family and friends in the Netherlands was a part of my daily routine.

‘Last Letter’ refers to the idea that the post office is entering a new stage in history. Part of its history has been cut off or made obsolete. It occupies a new purpose now, searching for other ways of transmitting messages. In this transition a certain chapter closes.

I collected some of these postcards from my Dutch family members that were sent from Indonesia to the Netherlands in the 1940s. Some postcards and envelopes I found in various archives still bear stamps from the 18th and 19th centuries. This collection of postcards and handwritten envelopes shows certain aesthetic conventions that have lasted for centuries, but which will not be carried on by the generations to come.

How were you received as an artist when you first moved to Indonesia, and how does the art scene differ now?

When I came as a student in 1984, I studied at the IKJ, the Jakarta Art Institute and ISI, the Indonesian Institute for the Arts in Yogyakarta. The art scene was so much smaller than it is now and I directly felt part of the discussions and developments through my engagement and involvement. The artists and lecturers were very open, and I felt I was in a place to look at how art was part of their daily reality.

This was forty years ago, and when I founded Cemeti together with Nindityo Adipurnomo in 1988, it became more like a laboratory to try things out in a non-established art scene, with discussions around post-modernism and the rise of contemporary art and curators. A small group of artists was at the forefront to comment and reflect on the dictatorial regime and social circumstances. Many art circles existed alongside each other, but everybody knew each other and respected each other.

Nowadays there are so many artists and artist communities. Although connected through Instagram and Facebook, there is less interaction and only safe play within each circle. There are far more possibilities for young artists’ development, like residencies, workshops, and collectors that support young artists’ works, some private museums, etc. But what is lacking is a critical foundation. There is not one art magazine left, there are no art critics as such. The dynamics of discussions and discourse are created by the artists, curators, and art workers.

When creating works that involve your Dutch heritage/culture, what is the process like for you having lived in Indonesia for nearly 40 years now?

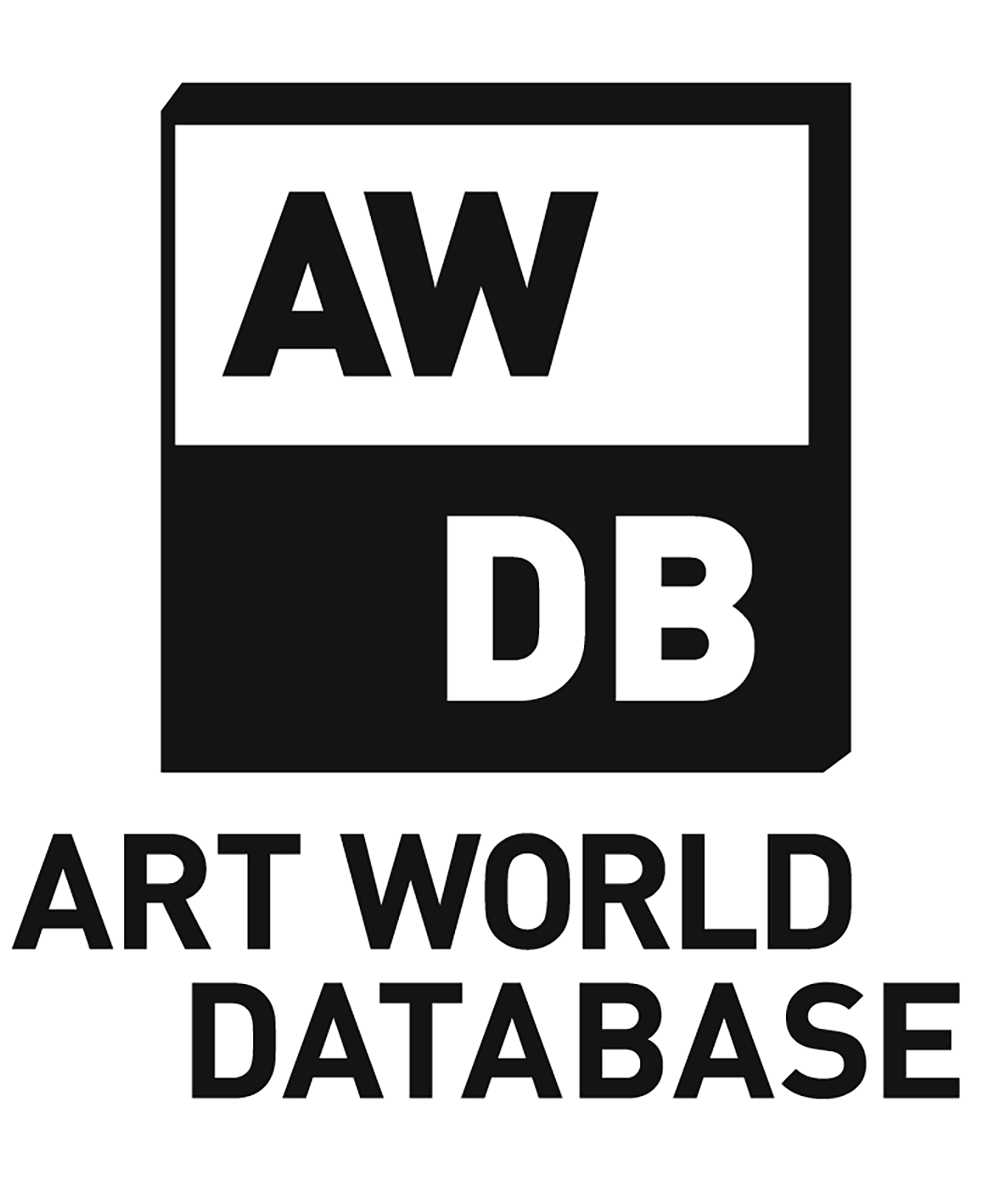

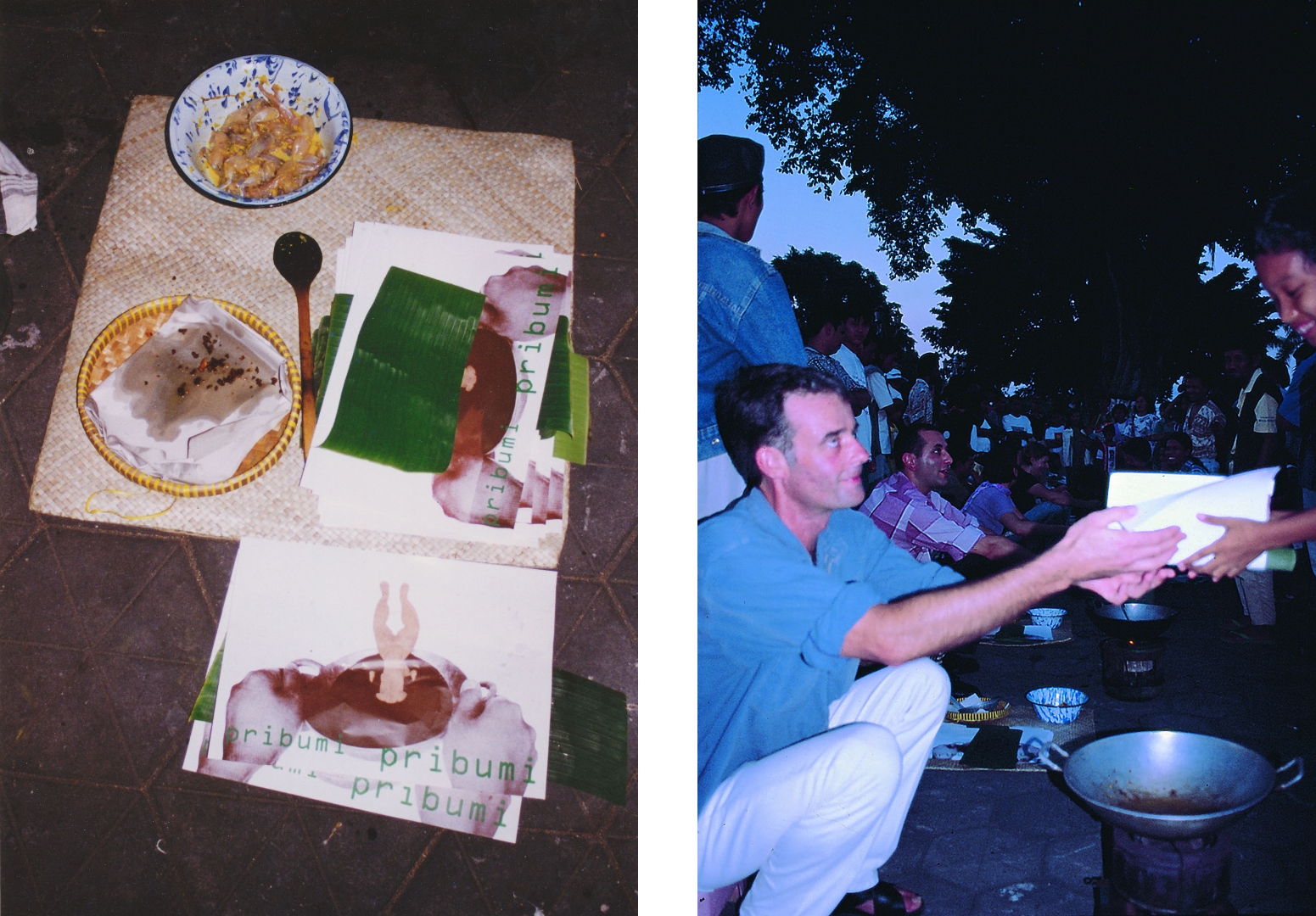

The colonial history is inextricably linked with today’s Indonesia. Through some of my work, I try to communicate different aspects that reflect the current social and political circumstances in relation to the past. For example in ‘Pribumi – Pribumi’ (1998), a performance involving frying frog legs along the street and serving the public this “haram” food, after what happened a few weeks before to the ethnic Chinese community, in the aftermath of the Suharto regime and its riots. It was my first political work, with the urge as a Dutch to act, because the colonial system created a discriminatory position of the Chinese community under the Suharto regime.

Another work is ‘A Blinkered View – High Tea Low Tea’ (2013) and ‘Lords Of The Tea’, (2012), where I looked into tea production and plantations and concluded that not much has changed since the colonial past. The high-quality tea is still for export and locals drink the rough tea leaves, which we find in the supermarkets, warungs and tokos.

Note to reader: The word “haram” means forbidden by Islamic law. A “warung” is a type of family-owned business in Indonesia and a “toko” is a type of retail shop found in Indonesia and the Netherlands. “Pribumi” means native Indonesian or “first on the soil”.

Food is another recurring theme in your work in which you explore multifaceted symbolisms, such as in ‘I Eat You Eat Me’ or ‘Feeding the Nation’. What about food keeps bringing you back to it?

I continue to look for ways to bridge the message that I have in my work to the audience and one important idiom I use is food. Food opens up communication and understanding. As a direct human need, it connects and creates new experiences of human habits. But food also very much relates to power structures, religion and the environment.

Naturally, when creating costumes, the form of the human body repeatedly appears; do you find this at all restricting when creating new projects?

The work is meant for humans to be seen with human eyes, with human proportions and perspectives. The materials and shapes of the wearables very much relate to the issues that I want to address and the choices of these are directly related to the concept of the work. And the work to be worn or held, creates a direct physical connection with the person looking at it. Some of my work is also participatory, able to step into it or put it on.

Through my work, I hope to raise specific issues and create awareness about some aspects, such as discrimination, gender inequality, environmental issues, and power structures. This is also why I still like to work with costumes, performances, and specific settings because it is a very direct way of connecting to the public and addressing those issues in a subtle way. I explore the physical appearance of the work/costume, the wearer, and the person who stands in front of it.

‘Surat Terakhir/Last Letter’ will be presented by Baik Art at ArtSG 2025 which will take place 17-19 January at Marina Bay Sands, Singapore. For more information, please click here.

INTERVIEW COURTESY OF ART WORLD DATABASE AND MELLA JAARSMA, JANUARY 2025